Palau’s Natural Resources

What are natural resources? How are they used? How are they extracted?

Natural resources are “any biological, mineral, or aesthetic asset afforded by nature without human intervention that can be used for some form of benefit, whether material (economic) or immaterial.”1 Natural resources can therefore range from immediate products of nature such as wood, nuts, berries, or medicinal plants to ecosystem services.

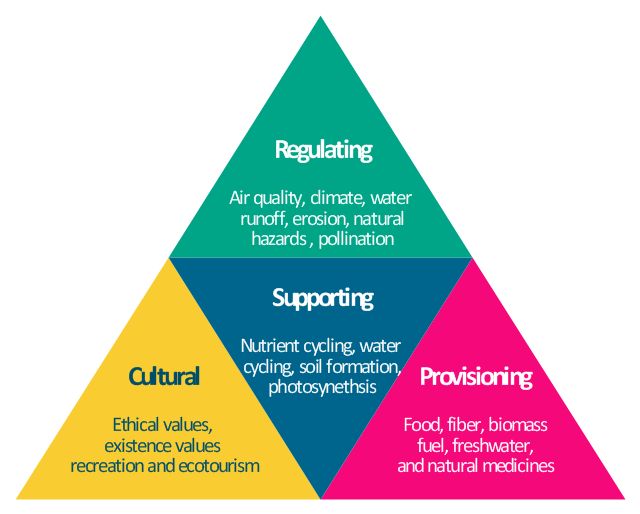

Ecosystem services are “any positive benefit that wildlife or ecosystems provide to people.”2 There are four types of ecosystem services: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting.2 (See Figure 1.) Provisioning ecosystem services are any material or energy outputs from an ecosystem.3 This includes fruits, trees, fish, livestock, drinking water, timber, wood fuel, natural gas, oils, and other plants.3 Regulating ecosystem services are any services that moderate or control ecosystem processes, such as carbon sequestration, pollination, regulation of soil quality, purification of air and water, temperature moderation, erosion and flood control, and more.3 Cultural ecosystem services are non-material benefits that people gain from their interactions with environmental spaces.4 Examples of cultural ecosystem services are: recreation and tourism, cultural heritage, landscape aesthetics, and spiritual and religious significance.4 Finally, supporting ecosystem services are the underlying natural processes that sustain ecosystems, such as photosynthesis, nutrient cycling, the creation of soils, genetic and biological diversity, and the water cycle.2 Watch this video for a quick summary on each of the ecosystem services.

Provisioning ecosystem services are what are typically thought of when referring to natural resources. These natural resources can be used in many ways; they can be sold for economic profit, used to make food, used to make energy, used to make resources, and used as raw materials for the production of other goods.5 The extraction of these natural resources, or the “withdrawing of materials from the environment for human use,” must be done carefully and consciously in order to be sustainable.6 This is because human innovations and the growing demands of an increasing global human population have led to us extracting resources quicker than the environment can renew them.6 This over-extraction has led to many environmental problems globally, such as the destruction of habitats and deforestation, the extinction of species, the pollution of the environment, the decrease of soil quality, the increase of erosion, the reduction of nutrient levels and freshwater availability, and more.6 It has also led to social problems such as colonialism, which was often spurred on by a desire to gain control over desirable natural resources that are unique to certain areas of the world.7

What, then, does sustainable natural resource extraction look like? Most basically, sustainable natural resource management involves using natural resources for current generations in such a way that the resources are not fully depleted and will be able to support future generations. In other words, the sustainable use of natural resources balances “maintaining the long-term use of resources while maximizing social benefits and minimizing environmental impacts.”8

So, what natural resources does Palau have? And how are they being used and extracted?

Palau has many natural resources. Most namely, Palau is well known for its many ecosystems and the various wildlife, plants, and activities that are associated with each ecosystem. Palau’s forests, for example, offer not only provisioning ecosystem services by acting as a source for timber and firewood, but also as cultural, regulating, and of course supporting ecosystem services (through photosynthesis, etc.).9 A cultural ecosystem service offered by Palau’s forests include the use of their wood by locals to create osmangel boxes, which are used to store traditional money, and kabekel, or canoes.9 (See Figure 2.) A regulating ecosystem service offered by Palau’s forests, such as mangroves, are their ability to filter the water of reefs and fisheries around the island.9

Palau is also the home to many different species of plants and animals that provide many ecosystem services, as well. Plants are used for medicine, or as weaving materials.9 Animals such as forest birds and bats are hunted for local commercial sale and subsistence.9 And, crops such as sweet potatoes, cassava, bananas, and other fruits are all consumed by locals and tourists.9 One crop that is especially important to Palau is taro. It is not only eaten, meaning it offers a provisioning ecosystem service, but also crucial to Palauan local tradition, meaning it offers a cultural ecosystem service.9 This is because taro is customary in food exchange between local clans, so much so that there is even a Palauan proverb that says “amesei a delal a telid,” or “the taro patch is the source of breath.”9 Wetlands used in taro farming also help maintain water quality by controlling erosion and help maintain bird diversity, meaning taro offers a regulating ecosystem service, too.9 (See Figure 3.)

Arguably, Palau’s most fruitful and abundant sources of natural resources are its marine ecosystems. The main provisioning ecosystem service offered in these marine ecosystems are fish and other sea life, which are both sold in local markets and restaurants, as well as consumed for subsistence.9 Some of the kinds of marine animals that are present in and around Palau include clams, sea cucumbers, crabs, octopus, squid, giant clams, rabbitfish, unicornfish, and surgeonfish.9 Palau’s marine ecosystems offer many cultural ecosystem services. This is primarily because a majority of Palau’s tourism centers on snorkeling, scuba diving to see Palau’s barrier reefs, and recreational sport fishing.9 A popular tourist attraction in Palau is the Jellyfish Lake, which is a marine lake that is home to millions of golden jellyfish.9 (See Figure 4). In addition to tourism, another cultural ecosystem service that Palau’s marine ecosystems offer are the value and tradition associated with many of their fauna. Sea turtles, dugong, sting rays, humphead parrotfish, and humphead wrasse hold especially important cultural value to indigenous Palauans.9 Dugong meat and bones act as a symbol of power for high clans and their leaders, and turtle shells, or toluk, have been, and still are, part of the traditional exchange system among Palauan clans.9 Another cultural ecosystem service that comes from Palau’s marine ecosystems is the research that is done in Palau to study their biodiversity by organizations and centers such as the Palau International Coral Reef Center, the Palau Mariculture Demonstration Center, the Palau Community College Cooperative Research and Extension Program, the Coral Reef Research Foundation, the Palau Conservation Society, the Nature Conservancy, Palau’s Bureau of Marine Resources, and Palau’s Office of Environmental Response and Coordination.9

Unfortunately, although Palau has dedicated a lot of its governmental resources towards the protection of its natural resources, there have still been some unsustainable extraction practices, such as overharvesting, illegal fishing, and extensive land and coral dredging, carried out by individuals and companies.10

Who are the stakeholders?

An environmental stakeholder is “a person with an interest or concern in environmental activities.”4 It is important to identify stakeholders when addressing an environmental problem, because they are the institutions, people, agencies, or organizations that can affect (and are affected by) the problem. In the case of Palau, we must consider those who have a stake in benefitting from and protecting Palau’s natural resources. Significant stakeholders are: local Palauans (as they depend on the plants and animals of Palau for their subsistence, economic growth, and cultural values9), tourists (as they are drawn to Palau by its many natural resources and the ecosystem services they offer9), Palau’s Bureau of Tourism (as it wants to protect Palau’s natural resources that are bringing in all of the tourists9), Palauan restaurants (which depend on fishing and farming of Palau’s wildlife), and the many research organizations and centers that are located in Palau to study its biodiversity (eg. the Palau International Coral Reef Center, the Palau Mariculture Demonstration Center, the Palau Community College Cooperative Research and Extension Program, the Coral Reef Research Foundation, the Palau Conservation Society, the Nature Conservancy, Palau’s Bureau of Fisheries, and Palau’s Office of Environmental Response and Coordination9).

What solutions are being implemented to stop unsustainable resource extraction in Palau?

One solution to Palau’s unsustainable resource extraction practices is the UN Environment project “Advancing sustainable resource management to improve livelihoods and protect biodiversity in Palau.” Read more about the project here. The project is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and executed by Palau’s Ministry of Natural Resources, Environment and Tourism.11 It aims to support Palau’s governance and management of land and marine ecosystems by engaging and involving local people in environmental decision-making, with the purpose of improving Palau’s protected areas.11 More specifically, the project “[implements] sustainable land management through improved coordination mechanisms at all levels of government and between different initiatives.”11

Another solution to Palau’s resource extraction issues is the Great Barrier Reef Foundation’s Resilient Reefs Initiative. This initiative is part of a global climate change program started by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation that helps reefs adapt to the impacts of climate change and local threats.12 The initiative collaborates with Palauan locals and their cultural and traditional knowledge, so that Palau’s reefs will be better protected.12 (See Figure 5.) Locals are involved in every step of the initiative’s work in Palau, as its goal is to “conserve the environment while continuing to provide communities with access to natural resources.”12

A third solution to Palau’s resource extraction management is its Shark Sanctuary, which was started in 2009 but continues to be maintained and effectively run.12 Palau is the first country to ever create a shark sanctuary, forbidding all commercial shark fishing within Palau’s waters.13 Overall, the sanctuary covers about 600,000 square kilometers of ocean.13 The sanctuary was created in the hopes of protecting Palau’s 135 endangered or vulnerable shark and ray species.13 This was not only to preserve and protect biodiversity, but also to protect the country’s tourism sector, as many tourists are interested in recreational activities involving the viewing of Palau’s many species of sharks.13 Watch a short docu-film on the Shark Sanctuary here.

Are there any barriers to these solutions?

There are a few barriers to the UN Environment project “Advancing sustainable resource management to improve livelihoods and protect biodiversity in Palau.”11 The first is cooperation between all of the stakeholders involved in the project, as its intention is to involve locals, government, and initiatives, each of which may have different objectives in mind in terms of resource management and strategies.11 Locals, for instance, may aim to protect resources relevant to their tradition and cultural practices, whereas corporations may aim to protect resources that they know will bring them great profit.9 Another barrier is that as Palau’s population continues to grow, the ways that resource management must be carried out need to adapt to accommodate supporting a much larger amount of people.14

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation’s Resilient Reefs Initiative also has a few barriers. Foremost, climate change remains a major threat to Palau’s reefs even with greater protection efforts implemented by the initiative.12 Read this article to learn more about how climate change impacts reefs. This impact is increasingly evident as there are ongoing declines in seagrass coverage, coral bleaching events, and overfishing in inshore areas near Palau’s reefs.12 (See Figure 6.) The fact that it is hard to manage declining fishing stocks while also ensuring local communities can keep their cultural ties and access to fish is also a barrier, as such a balance is hard to objectively find and maintain.12

Palau’s Shark Sanctuary faces enforcing its ban on shark fishing as its predominant barrier.13 Palau currently has only a minimal number of patrol boats and skiffs that can scan its oceans for illegal fishing vessels.13 To make matters worse, many areas of Palau’s oceans are remote, with very few inhabitants nearby.13 The profits associated with the shark fishing business have very high margins, meaning that individuals find it worth risking being apprehended, just for the chance of making money.13

So, are these solutions sustainable?

The definition of sustainability that I will use for this analysis is outlined in my Place-Based Project Essay. Please click here to view this definition.

The UN Environment project “Advancing sustainable resource management to improve livelihoods and protect biodiversity in Palau” is a pretty sustainable solution.11 This is largely because of how it engages with so many stakeholders to create resource management strategies that meet all people’s needs.11 The project even states that its goal is to bring “together stakeholders from different backgrounds to coordinate their efforts on the management of the environment and natural resources.”11 This meets the definition’s call for “an inclusive and transparent process that includes a diversity of stakeholders, considers the intersectional nature of sustainability… [and] empowers individual and collective action.”11 One of its shortcomings is that the project does not clarify any measurable indicators for assessing its success, as the definition necessitates.11

According to our definition, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation’s Resilient Reefs Initiative is a largely successful sustainable effort. It involves locals and values their cultural and traditional knowledge, meaning it includes “a diversity of stakeholders” and “considers the intersectional nature of sustainability,” as well as “considering traditional practices.”12 On top of that, the initiative’s entire goal, to help reefs adapt to climate change and local threats, meets the definition’s call for protecting and restoring “the health of natural ecosystems,” and supporting “climate change mitigation and/or adaptation.”12 Finally, as mentioned before, the initiative even clarifies that it wants to “continue to provide communities with access to natural resources,” therefore serving “to meet the social and economic needs of present and future generations.”12

Lastly, Palau’s Shark Sanctuary overall meets our criteria for sustainability rather sufficiently. First and foremost, this is because of its implementation of technology as a solution to its challenges in regulating all of Palau’s oceans.13 The sanctuary has recently begun developing and using tracking devices and satellite data to monitor activity at sea, accordingly taking advantage of a “growing body of scientific information.”13 This alone meets one of the definition’s criteria. Having said that, the sanctuary released a statement that its efforts are based on the principle that “we do not inherit the earth from our parents, we borrow it from our children,” meeting the definition’s call for meeting “the social and economic needs of present and future generations.”13

What assets does Palau have regarding these solutions?

Assets that are mentioned in the UN Environment project “Advancing sustainable resource management to improve livelihoods and protect biodiversity in Palau,”11 the Great Barrier Reef Foundation’s Resilient Reefs Initiative, and the Shark Sanctuary include: the United Nations, the Global Environment Facility (GEF), Palau’s Ministry of Natural Resources, Environment and Tourism, local Palauans,11 and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.11

These assets, along with many others, can be viewed here in my asset map.

References

1The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, April 12). Natural resource | Definition, Examples, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/natural-resource

2Ecosystem Services. (n.d.). National Wildlife Federation. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Understanding-Conservation/Ecosystem-Services

3Ecosystem Services | USDA Climate Hubs. (n.d.). https://www.climatehubs.usda.gov/ecosystem-services

4Cultural ecosystem services, values and benefits – Forest Research. (2024, April 17). Forest Research. https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/research/cultural-ecosystem-services-values-and-benefits/

5U.S. EPA & Office of Solid Waste Reduction & Recycling. (2005). Natural resources. In The Quest for Less: A Teacher’s Guide to Reducing, Reusing and Recycling [Book]. https://scdhec.gov/sites/default/files/Library/OR-0689.pdf

6Resource extraction – Understanding Global Change. (2020, September 11). Understanding Global Change. https://ugc.berkeley.edu/background-content/resource-extraction/

7World Social Science Report 2016: Inequality and Natural Resources in Africa. (2016). In United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. International Social Science Council. https://en.unesco.org/inclusivepolicylab/sites/default/files/analytics/document/2019/4/wssr_2016_chap_09.pdf

8Bansard, J., & Schröder, M. (n.d.). The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: the Governance challenge. International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://www.iisd.org/articles/deep-dive/sustainable-use-natural-resources-governance-challenge\

9Palau Value. (n.d.). Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.cbd.int/financial/values/palau-value.doc%23:~:text%3DFarmed%2520crops%2520&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1714164488121794&usg=AOvVaw1p0AiuUCuEgdbqzOGl2Ufn

10Palau. (2021, May 17). Pacific RISA – Managing Climate Risk in Pacific Islands. https://www.pacificrisa.org/places/republic-of-palau/

11United Nations Environment Programme. (n.d.). Rich in biodiversity, Palau looks to protect its most precious resource. UNEP. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/rich-biodiversity-palau-looks-protect-its-most-precious-resource

12Protecting oceans the Palauan way. (2023, May 25). Great Barrier Reef Foundation. https://www.barrierreef.org/news/news/protecting-oceans-the-palauan-way

13Morisod, F. (2021, December 29). The first shark sanctuary. Master Liveaboards. https://masterliveaboards.com/the-first-shark-sanctuary/14Rodriguez, S., PhD. (2024, March 21). Five Critical Challenges to Sustainable Development – Herrmann Global. Herrmann Global. https://herrmannglobal.com/2024/02/12/five-critical-challenges-to-sustainable-development/